Rob Finch and I have spent the last month or two working on a multi-part story about a former wrestling star who lost track of his baby daughter nearly three decades ago. Here's the first part. I'll post the second and Rob's amazing video in the next few days.

No one boos Mean Mike Miller anymore.

In the days when Portland Wrestling packed thousands into arenas every Saturday night, Miller was the villain everyone loved to hate. He sauntered to the ring to the tune of George Thorogood's "Bad to the Bone," his shoulder-length hair waving behind him. Fans threw lit cigarettes at him. Ringside girls -- the Rosies -- cursed his name.

The fights ran in prime time every week for 38 years. The scene is Portland lore -- wrestlers became stars; kids clamored for autographs. Then, two decades ago, it ended, when the steroid-inflated soap opera of the World Wrestling Federation edged Portland's show out of the market.

Miller lost the jeers when Portland lost wrestling.

But now, after a few failed restart attempts and decades of quiet gyms, Portland wrestling is in the middle of something like a comeback. New leagues like Blue Collar Wrestling and DOA host regular matches. Rowdy Roddy Piper plans to debut an in-studio revamp of the old company this month on KPTV. Portland is ready, some say, for a return of the good, the evil, the suplexes and the pins that kids still imitate at home.

And Mike Miller? He's been out of the ring for a while, but he's back too, teaching the young generation of wrestlers how to body-slam, hip-toss and take a chair to the back of the head.

Even better, he will slip through the ropes one last time this Sunday night. And when he does, he won't be doing it for the boos -- though they once gave him the only rush that mattered. Mean Mike will do it for love.

A Tennessee boy

James Michael Hillman had 35 bucks in his pocket the day he became Mike Miller.

Like most boys who grew up in Whiteville, Tenn., he had few prospects. He never dreamed of being anything because no one he knew was anything. After high school, he drove a truck for the local factory.

In 1978, a promoter spotted him -- 6-foot-2 and barrel-chested, but otherwise physically insignificant -- and offered him a spot in a yard brawl. Back then, you didn't have to be special to wrestle. You just had to be willing.

The promoter changed his name to Mike Miller. The "Mean" came later.

He worked his way up through the Southern towns, fighting for $800 a weekend. He met a girl in New Orleans. They married. When she gave birth to an 8-pound baby girl, Yolanda, he knew he wanted to make an even better life for the family.

Back then, every little town had its own wrestling dynasty. Portland promoter Don Owen built Portland Wrestling into one of the most renowned. Superstars such as Andre the Giant, Ric Flair and Jesse "The Body" Ventura performed in front of thousands in the Portland Sports Arena.

Mike Miller didn't cuss, had never taken so much as a sip of whiskey, but the league needed more bad guys to add to a roster that included Playboy Buddy Rose and Rowdy Roddy Piper.

Miller grew his hair long, plastered a pair of black tights over his now muscular thighs and set his face into a permanent grimace.

"It was the dark side of me," he said. "I'd grown up such a Southern Baptist kid, so nice, so afraid of Hell. Now I could play it out."

Other wrestlers were faster, more athletic. Mean Mike brooded around the ring, a brute with a heavy fist. He stayed off the turnbuckle, wearing down opponents with grueling headlocks and arm twists. He painted an old 2x4 black, wrapped it in a chain and named it Lucille.

"He doesn't wrestle too scientifically," Dutch Savage said in 1982, "but he gets the work done in the ring."

Miller's career had finally taken off by 1983. But in a Centralia fight, his foot awkwardly caught an opponent's leg. The impact sounded like a tree thudding against the earth.

He couldn't wrestle, and the money dried up. Things turned. Miller's wife took Yolanda and headed back South. By the time he healed, he had lost track of his family. His wife moved on, changed her daughter's last name and never mentioned Mike Miller again.

Yolanda begged, but her mom refused to reveal her dad's stage name. "His name was James Hillman. He's a rolling stone, and he's gone," the mother said.

In the decade he wrestled in Portland, Miller busted his collarbone, broke his nose and separated his shoulder. Nightclubs held tables for him. Women went after him.

"The first time I ever seen him, I just fell in love with his hair," said Marion Martin, a fan who once stole his bloody shirt from a little girl. "They said he was mean, but with hair like that, he could do no wrong."

Miller remarried, raised a son and daughter and settled in for the good life.

The fight turns

Portland Wrestling aired its last match a week after Christmas 1991. Mean Mike rolled his opponent into a Boston Crab but lost when Ricky Martel wrapped him in a small package. Referee Sandy Barr slammed his palm against the mat. "One. Two. Three!" Miller stumbled through the Memorial Coliseum, and the crowd booed.

Some Portland stars went to the WWF. But Mean Mike didn't have the right bodybuilder, heartthrob look. He went back to driving trucks, moved logs off Mt. Hood. He worked as a bouncer and a prison guard. Finally, he went back to being nobody James Hillman and left for Tennessee.

"It was worse than a death," he said. "I didn't want to watch wrestling. Even if the TV was on, and wrestling was on, I cut it off, it hurt so bad."

But the WWF, now known as World Wrestling Entertainment, just kept growing. About 850,000 people bought Wrestlemania, its biggest event, on pay-per-view this year.

That hasn't been lost on local promoters. So last year, they launched an effort to rekindle Portland's famed wrestling spirit here. Blue Collar Wrestling began holding matches at the North Lombard Eagles Lodge.

The Blue Collar Wrestlers work the West Coast to take home a few hundred bucks a weekend. But the young fighters were reared on WWF wrestling -- off-the-rope acrobatics with little attention to story, said Blue Collar Wrestling co-owner Tex Thompson. They needed to work out storylines. They needed better choreography. They needed Mike Miller.

James Hillman returned to Portland in 2011. And as one of the Blue Collar wrestlers trolled YouTube for old fighting videos of his new mentor, he noticed a comment.

"Does anyone know how or where to find (Miller)," it read. "I have some important news to tell him about his daughter he had back in '81."

Reunions

That was all it took. They found each other, and Yolanda Montero and her wrestler dad talked every night for three hours. She had lived in New Orleans until she was 20. Nothing in her life ever seemed to work out quite right. She made regular trips to the library, searching the Internet for her father.

Two months ago she came to Oregon, where she and her dad now share a Gresham apartment. In the videos Miller shows her of his heyday, she can see for herself the way the crowds loved to hate him.

"But I do get mad," she said. "Everybody's telling me what he did. All the wrestlers here have stories about seeing him. And I just wish I could have been there."

A month ago, over their morning coffee, Miller asked his daughter, "What if you saw your daddy wrestle now?"

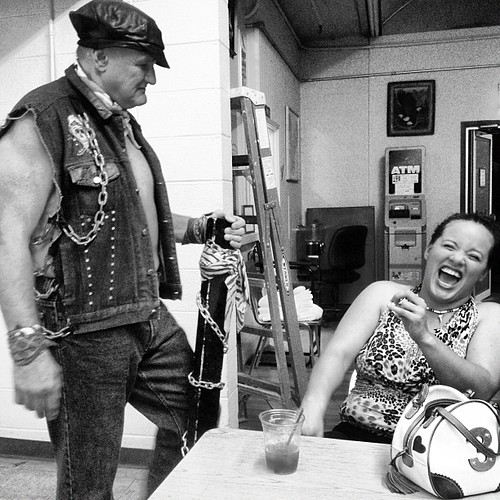

Miller still wears all black, but he keeps his hair cropped close now. His notoriously long frame is hunched slightly. A walk that once looked broody now looks like taking it easy. But he has no trouble getting in and out of the ring.

He began planning the story for his last fight a month ago. The nighttime security job he works wouldn't let him off one Sunday night, so he missed that night's matches. Psycho Sailor -- a bad guy whose raspy bark sounds like Popeye -- took the absence as a chance to mock the old man. He played "Bad to the Bone" and marched around, declaring himself meaner than Miller.

Last Sunday, Miller refereed Sailor's match. The Eagles Lodge draws crowds of about 40 now, but the place felt packed. Mean Mike emerged, and the opening guitar chords of "Bad to the Bone" shook the lodge. He handed Lucille to an old lady and started Sailor's fight.

Back and forth, Psycho Sailor and his opponents bloodied each other, while Miller kept an eye on them. Sailor bent a baking sheet over Cowboy Tex Thompson's head. Miller rushed in to keep the peace. Fans raced around the ring to stay with the action.

One of Sailor's minions stole Lucille from the old lady and rushed Miller with a menacing yowl. Sailor grabbed Miller and pinned his arms back.

Miller looked ready to take a face shot like in the '80s. But he ducked, yanked back Lucille and ran Sailor and his minions off like a pack of raccoons.

"Get on now," he hollered. "You want some of this? I'll see you in the ring next Sunday."

The whole charade took maybe 10 minutes. No one booed. The cheers, in fact, were deafening.

-- Casey Parks

![[seconds and decades]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh_tTMVKRz0jDrVLxSpQ0DZU4SvFB5GzxnXrrF4bXty5nK5bsdFLb9T2H1EpMNEKjTltmj59LpwdlQMvYjt4QSJWpnKrIMEvNB4TMViH-CnLnh5Sq3Td8_HnCzZIV4jyN9V86Ywveg6g42r/s1600/sandd2.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment