Mean Mike Miller's Last Match from Oregonian News on Vimeo.

They came to see the mean man.

The crowd of hundreds may not have been the mob the Portland Armory drew when Portland Wrestling peaked in the 1980s, but for the Blue Collar wrestling league, last week's matches played before a packed house.

Mean Mike Miller had come out of retirement. The fans had come to relive wrestling's glory days. Remember the time you turned on your tag-team partner? they asked. And what about the cage match? The famous elbow drop?

So many people came, Miller barely had time to talk to the one fan who mattered. The one who had never seen him fight.

Yolanda Montero, 31, never watched wrestling. She didn't care for violence, scripted or otherwise. But Sunday night she stood ringside for the match: her first, her father's last.

Connections

Mean Mike Miller lost his daughter 27 years ago, just as he became a star in the Portland Wrestling Circuit. He tried off and on through the decades to look for his daughter but never found her.

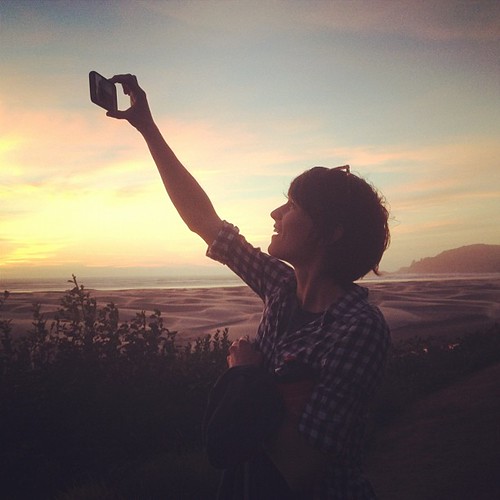

Then last year Yolanda, who had been looking for her dad for years, too, found an online video of him wrestling. Her brother posted a comment -- "Anyone know how or where to find him?" That was all it took. A Portland wrestler saw it, and father and daughter reunited.

She soon moved to Portland from Florida to be with her dad. They rented an apartment together. They stayed up late talking every night.

Neither was proud of the way they spent much of their lives. Miller had remarried and had other kids. But the wrestling life was a fast-paced one -- "sex, drugs and rock and roll," he said -- and some of his kids resented him for choosing wrestling over them.

"I haven't felt this way in a long time," Miller said. "I haven't felt like a father. And she's made me feel like a father."

The talks would never replace the years, though. Thousands of Portland Wrestling fans had followed Mean Mike's career, watched him saunter to the ring as George Thorogood's "Bad to the Bone" rattled their seats. All Yolanda had was videos.

One morning over coffee, Miller asked his daughter, "What if you saw your daddy wrestle now?"

A week ago Sunday at North Portland's Eagles Lodge, fans clamored for Miller. They brought homemade signs and t-shirts, angled for an autograph. We thought we'd never see you wrestle again, they said.

Yolanda said, "I thought I'd never see him at all."

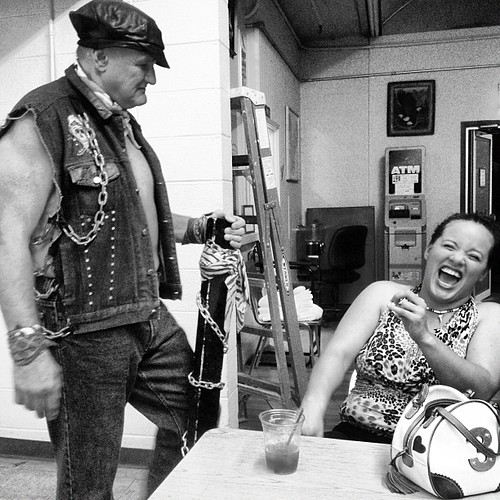

Her dad's fight against Psycho Sailor was the night's main event. When the bell rang, signaling the end of the third match, Miller tied a Harley Davidson bandana around Yolanda's curly hair.

He ducked into the bathroom to change into his wrestling clothes -- a black denim vest, chains and a black leather cap. He stepped out, flexed, then laughed at himself. It was his 61st birthday. His arms weren't quite the 19-inch behemoths they were when he made a name pile-driving and suplexing opponents.

He handed Yolanda his 2x4 -- named Lucille -- the one he once used against opponents. She would carry it to the ring then hold it on the sidelines.

The only time Yolanda had ever been in the spotlight was a track meet once. She wanted to throw up then, but this was worse.

She twirled the 2x4. She swatted at the air. But the board was heavier than it looked. It slipped, knocking against her new high-heel boots.

"How should I walk to the ring, Daddy?" she asked. "Should I strut?"

The bell rang again. The fourth match was over. Theirs would start soon. Mean Mike didn't want to enter the common way, so he and his daughter waited outside the lodge, in the rain, until they could crash through the front door.

The first notes of Bad to the Bone pounded the lodge. Yolanda took a sip of rum and coke to calm her nerves. Her dad waited, letting the first dozen bars play out as the crowd went crazy with anticipation.

They walked around the ring, shaking hands, hugging the fans who came to relive Portland's good ol' days. The saxophone solo that closes out "Bad to the Bone" had reached its peak before the duo ever made it halfway around the lodge.

Miller swung into the ring. Yolanda, holding Lucille and looking unsteady on the boots, stepped up to the ropes. But the spotlight no longer made her nervous.

"That's my daddy," she screamed.

Miller poked his opponent in the eyes, swung a few fists. He took a turnbuckle to the head then threw Psycho Sailor into the ropes and over his shoulders.

The match ended quickly. The mean man never hit the mat. With Sailor still dizzy from the spill, Miller grabbed Lucille from his daughter.

He clocked Sailor in the chin. The pin was quick and easy. Ringside, Yolanda did the funky chicken.

The bell rang. They hugged across the ropes. Then she stepped through, into the ring with her daddy.

-- Casey Parks

![[seconds and decades]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh_tTMVKRz0jDrVLxSpQ0DZU4SvFB5GzxnXrrF4bXty5nK5bsdFLb9T2H1EpMNEKjTltmj59LpwdlQMvYjt4QSJWpnKrIMEvNB4TMViH-CnLnh5Sq3Td8_HnCzZIV4jyN9V86Ywveg6g42r/s1600/sandd2.jpg)