Saturday, March 31, 2012

Friday, March 30, 2012

World can't hold me, too much ambition

Most days at work, I'm writing government explainers, development updates or controversies of the day. But every once in a while I have a chance to write a story like this:

HILLSBORO -- After five years of giving and taking punches, 19-year-old Gabe Pineda was done. He left his gloves hanging near the ring at Chief CornerStone, the boxing gym where he'd practiced nearly every day since he was 13.

As he left the sweltering basement gym in the spring of 2010, he recalled a dream he had as a little kid. He was walking somewhere. Spotlights shone on his face from every angle. If he stayed at the gym, boxing might bring him that fame. After all, he was already a champion, having won Oregon's amateur tournament three years in a row.

But being a boxer meant skipping high school parties, avoiding his favorite foods.

Never mind the spotlight, he thought. He wasn't coming back.

'Boxing picked him'

The boxers at CornerStone call Pineda "Ducky," a nod to his feet-out, waddle way of walking. He's 5-foot-6 and fluctuates between 132 and 141 pounds. That's light welterweight range, but his stance implies a density beyond his mass. He's broad-shouldered, a solid trapezoid with cut arms.

"Boxing picked him," said his coach, Rudy Aguero. "He's built like a boxer."

Ever since that childhood dream of spotlights, Pineda had wanted to become a professional athlete. He gravitated first toward soccer, his father's sport. But as he watched Felix Trinidad defeat Oscar De La Hoya in a historic television match in 1999, Pineda abandoned soccer for boxing.

"Seeing a Latino fall like that was so hard for me," he said.

Pineda wanted to fight, but Hillsboro didn't have a youth gym. By the time he met Aguero at J.B. Thomas Middle School, Pineda's parents were divorcing. His father moved out. The teenager was hurt, angry. He wanted to disappear inside a ring.

Aguero, 47, had been a professional boxer in California before retiring in 1994 to become a youth pastor. He and his wife moved to Hillsboro in 2003 and opened a gym, using tape to mark the boundaries, inside a martial arts club. The next year, they moved to the old gymnasium inside J.B. Thomas, where they met Pineda one day in the halls.

The short and slim 13-year-old who wore his hair in an Eraserhead-style shock didn't otherwise stick out from the crowd of youngsters wanting to join the new gym. Eight months in, though, Aguero noticed that Pineda seemed smarter than other boxers. He anticipated other fighters' moves.

Pineda is a tactician, Aguero said. He excelled at science and math. He was the only freshman in his geometry class at Hillsboro High School. In the ring, he saw opponents as combination locks, waiting to be picked.

"Most boxers have a rhythm," Pineda said. "If you can break that rhythm, you can break them."

READ THE SECOND HALF OF THE STORY ON OREGONLIVE HERE.

HILLSBORO -- After five years of giving and taking punches, 19-year-old Gabe Pineda was done. He left his gloves hanging near the ring at Chief CornerStone, the boxing gym where he'd practiced nearly every day since he was 13.

As he left the sweltering basement gym in the spring of 2010, he recalled a dream he had as a little kid. He was walking somewhere. Spotlights shone on his face from every angle. If he stayed at the gym, boxing might bring him that fame. After all, he was already a champion, having won Oregon's amateur tournament three years in a row.

But being a boxer meant skipping high school parties, avoiding his favorite foods.

Never mind the spotlight, he thought. He wasn't coming back.

'Boxing picked him'

The boxers at CornerStone call Pineda "Ducky," a nod to his feet-out, waddle way of walking. He's 5-foot-6 and fluctuates between 132 and 141 pounds. That's light welterweight range, but his stance implies a density beyond his mass. He's broad-shouldered, a solid trapezoid with cut arms.

"Boxing picked him," said his coach, Rudy Aguero. "He's built like a boxer."

Ever since that childhood dream of spotlights, Pineda had wanted to become a professional athlete. He gravitated first toward soccer, his father's sport. But as he watched Felix Trinidad defeat Oscar De La Hoya in a historic television match in 1999, Pineda abandoned soccer for boxing.

"Seeing a Latino fall like that was so hard for me," he said.

Pineda wanted to fight, but Hillsboro didn't have a youth gym. By the time he met Aguero at J.B. Thomas Middle School, Pineda's parents were divorcing. His father moved out. The teenager was hurt, angry. He wanted to disappear inside a ring.

Aguero, 47, had been a professional boxer in California before retiring in 1994 to become a youth pastor. He and his wife moved to Hillsboro in 2003 and opened a gym, using tape to mark the boundaries, inside a martial arts club. The next year, they moved to the old gymnasium inside J.B. Thomas, where they met Pineda one day in the halls.

The short and slim 13-year-old who wore his hair in an Eraserhead-style shock didn't otherwise stick out from the crowd of youngsters wanting to join the new gym. Eight months in, though, Aguero noticed that Pineda seemed smarter than other boxers. He anticipated other fighters' moves.

Pineda is a tactician, Aguero said. He excelled at science and math. He was the only freshman in his geometry class at Hillsboro High School. In the ring, he saw opponents as combination locks, waiting to be picked.

"Most boxers have a rhythm," Pineda said. "If you can break that rhythm, you can break them."

READ THE SECOND HALF OF THE STORY ON OREGONLIVE HERE.

Thursday, March 29, 2012

All day you've been linked by the light

Since we’re not young, weeks have to do time

for years of missing each other. Yet only this odd warp

in time tells me we’re not young.

Did I ever walk the morning streets at twenty,

my limbs streaming with a purer joy?

did I lean from any window over the city

listening for the future

as I listen here with nerves tuned for your ring?

And you, you move toward me with the same tempo.

Your eyes are everlasting, the green spark

of the blue-eyed grass of early summer,

the green-blue wild cress washed by the spring. -- a. rich

for years of missing each other. Yet only this odd warp

in time tells me we’re not young.

Did I ever walk the morning streets at twenty,

my limbs streaming with a purer joy?

did I lean from any window over the city

listening for the future

as I listen here with nerves tuned for your ring?

And you, you move toward me with the same tempo.

Your eyes are everlasting, the green spark

of the blue-eyed grass of early summer,

the green-blue wild cress washed by the spring. -- a. rich

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

Tuesday, March 27, 2012

From this position, I can see the whole place

Michelle and I went to the Oregon desert for the weekend. We saw lots of wild horses and, miracle upon miracle, the sun.

Wednesday, March 21, 2012

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

like lately, like this morning, as I was leaving

Monday, March 19, 2012

Monday, March 12, 2012

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

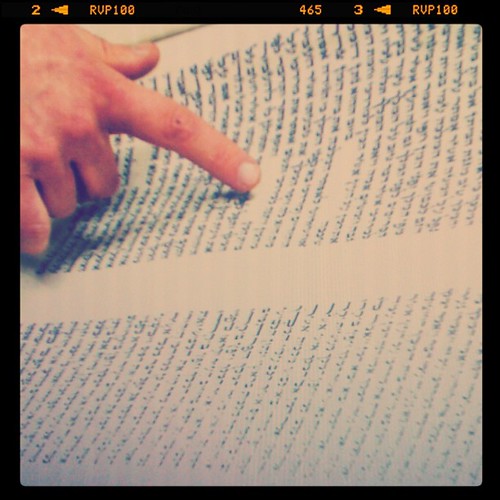

This story was really fascinating to report, but I think if I had had another week, I could have written it much better. Still, the family's story is very interesting to me, so I'll share the piece I wrote on their work.

No one met Rabbi Menachem Rivkin at the airport the night he, his wife and 6-month-old twins flew from New York to Portland. No one brought a housewarming gift to their Hillsboro home or joined the family for Friday night prayers.

That was the point. Hillsboro was a city without a synagogue. Its grocery stores had no kosher sections. Jews wanting community, a chance to be themselves without explanation, had to drive to Portland.

In that void, Rivkin saw opportunity, a chance to create, from scratch, a home for Hillsboro Jews. When the plane touched down after a full day of traveling, Rivkin was eager to start immediately. He didn't know a soul, but he had plans for a dozen different classes.

"I always want to spin the wheel faster than it naturally goes," he says.

Rivkin has spent five years laboring to create that community. He is on the verge of reaching his greatest milestone yet: The city recently granted his congregation, Chabad Hillsboro, a permit to build Hillsboro's first synagogue.

Like his father before him, Rivkin practices Chabad, a Hasidic movement that brings services to cities that lack a strong Jewish presence. He grew up in Israel and completed rabbinical studies in New York, where he met Rabbi Motti Wilhelm, whose father directs Chabad of Oregon. Hillsboro needed a Jewish community, Wilhelm told Rivkin.

Sometimes building a community takes no work at all.

As he strode across the Costco parking lot one afternoon soon after his arrival, Rivkin's appearance caught the eye of a young blond boy. Rivkin is Orthodox: A full beard shades his face, a wide-brimmed Borsalino hat perches atop his head. He was only 25 when he arrived in 2007, but his dress gave him an ancient air.

"Hey," then-7-year-old Aedan Mills-Koffel called across the parking lot. "I'm a Jew, too!"

READ THE REST ON OREGONLIVE HERE.

Thursday, March 8, 2012

Tuesday, March 6, 2012

Monday, March 5, 2012

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

![[seconds and decades]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh_tTMVKRz0jDrVLxSpQ0DZU4SvFB5GzxnXrrF4bXty5nK5bsdFLb9T2H1EpMNEKjTltmj59LpwdlQMvYjt4QSJWpnKrIMEvNB4TMViH-CnLnh5Sq3Td8_HnCzZIV4jyN9V86Ywveg6g42r/s1600/sandd2.jpg)